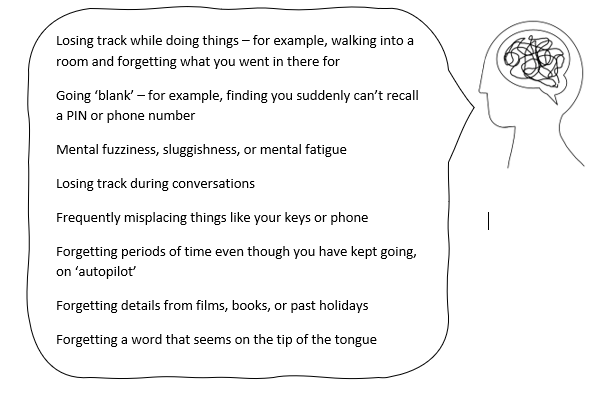

Functional cognitive disorder is a problem with memory or concentration that happens when the brain doesn’t work or function as we need it to. Functional cognitive symptoms are not caused by disease or damage to the brain, but they are coming from the brain.

Some people may have relatively mild functional cognitive symptoms, sometimes alongside other health problems. For other people, memory symptoms are the main problem that affects their day-to-day life, and the term functional cognitive disorder is used. Functional cognitive symptoms can be frightening. They can make normal activities like working and socialising much more difficult.

Some people are concerned that their problems might be caused by a type of dementia, like Alzheimer’s disease, or might be related to damage after an injury.

Deciding whether someone’s memory and thinking problems are the result of brain disease or damage, or whether they are functional cognitive symptoms, requires careful assessment.

However, it is possible to make a confident and accurate diagnosis of functional cognitive symptoms. Having a definite diagnosis can help people find ways to improve their symptoms.

This information is designed to help share what we know about this condition and to give you some ideas to help make sense of what is going on.

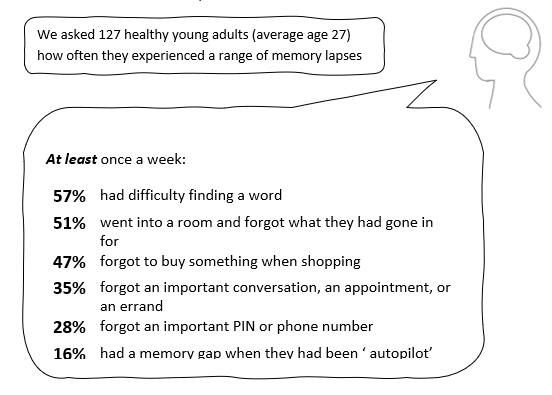

Functional cognitive symptoms are common. However, until recently doctors have described them using a lot of different terms, which can be confusing.

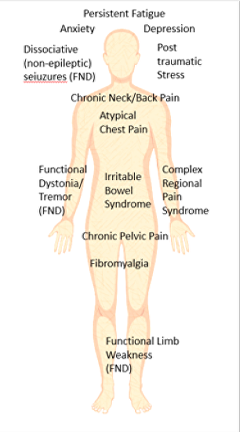

Functional cognitive symptoms can occur on their own. They are very common in people with other symptoms of functional neurological disorder (FND). FND is the name of a condition where people have a variety of neurological symptoms such as limb weakness or blackouts which are genuine and arise from a similar problem in nervous system functioning. They are also common in people with painful conditions, like fibromyalgia, and in conditions where people have severe fatigue. They can also be accompanied by anxiety and depression or sometimes be part of it. We will discuss this more later on.

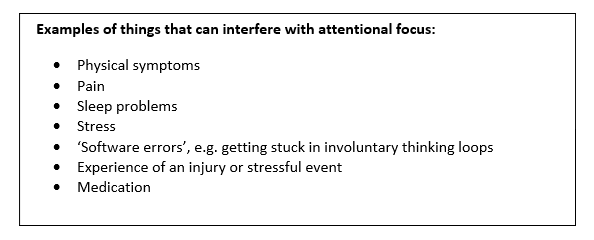

Functional cognitive symptoms can happen for several different reasons. Often, more than one underlying cause is present.

Functional cognitive symptoms can come ‘out of nowhere’, but can also start after an injury or traumatic event. Head injury or mild traumatic brain injury (sometimes called concussion) is a common trigger.

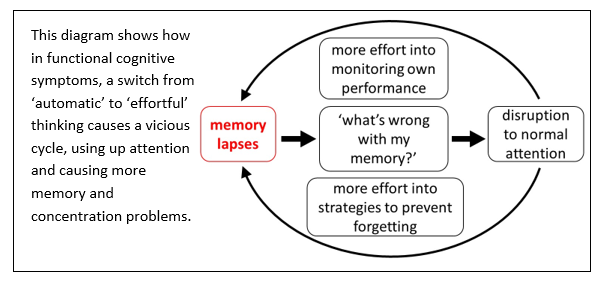

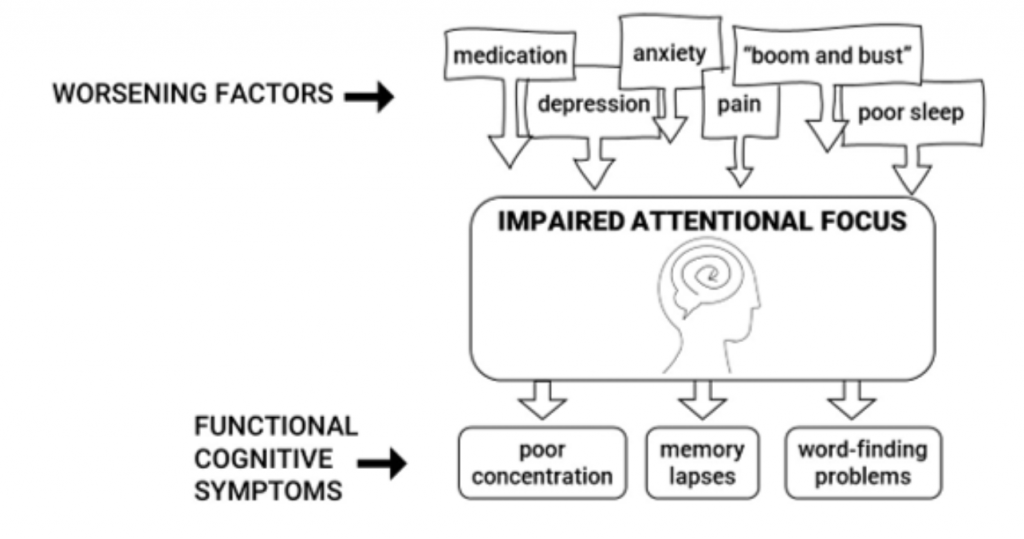

Most things that cause functional cognitive symptoms do so by interfering with a set of brain processes called attention.

Although our capacity to learn and store information is enormous, our attention is limited. We can only focus on a small amount of the world at one time. If you cannot focus attention on new information, you won’t be able to learn and remember that information.

Although the symptoms of functional cognitive disorder and dementia may seem similar, they have different causes. In dementia, memory symptoms are the result of damage to the brain areas involved in memory, as a result of progressive brain disease. In functional cognitive disorder, symptoms arise from changes in brain processing, and not due to damage or disease of the brain.

“Mild cognitive impairment” or “MCI” is a term that is sometimes used by doctors to describe patients with cognitive problems who don’t have dementia, but who may be at higher risk of developing dementia in future. However, “mild cognitive impairment” is only a description of symptoms and difficulties, and not a diagnosis of any specific disease.

Importantly, some people with functional cognitive symptoms might also be told that they have “Mild cognitive impairment”, especially if they struggle with memory tests. But people who doctors can clearly identify as having functional cognitive symptoms are less likely to develop dementia in the future than some other people with mild cognitive impairment.

It is really important for functional cognitive symptoms to be identified. This is because this changes the information that doctors will give you about your future risk of dementia, and because specific treatments might also be available that will help to improve your symptoms.

Functional cognitive symptoms are real. They are not “put on”, “imagined” or “all in the mind”.

For some people, depression or anxiety can be an important factor that may contribute to the development of functional cognitive symptoms. Even for people who are not depressed or anxious in general, worries about the cognitive symptoms can worsen their symptoms and make it harder to recover. Many people with functional cognitive symptoms are not depressed or anxious, but it is important to recognise depression and anxiety when they are also present, as treating these problems can help the symptoms to improve.

It is essential that you feel you have the correct diagnosis. If you don’t, it will be hard to put into practice the self-management strategies suggested here.

If you don’t feel you have functional cognitive symptoms, you need to look at on what basis the diagnosis has been made. Usually, it will be because the pattern of your symptoms matches the typical features of this condition. You do not need to be stressed to have functional cognitive symptoms. Perhaps the diagnosis didn’t make sense to you because the doctor suggested it was “stress-related”? There may have been a misunderstanding if that was the case. We know that some patients do have stress as a cause of their symptoms, but many don’t. So, whether you have been stressed or not is not relevant to the diagnosis.

If necessary, go back and speak to the person who made the diagnosis. Find out why they made it and see if you can gain more confidence in it.

•Are you on any medication that could worsen cognitive symptoms? Many types of medication, especially painkillers, and sleeping tablets, can worsen memory symptoms. If so, ask your GP or consultant to review whether these could be adjusted.

•Is your sleep pattern good? If not, try to follow “sleep hygiene” advice to improve this. Exercise can also improve our sleep and general well-being.

•Do you have any depression or anxiety symptoms? If so, ask your doctor if you might benefit from treatment for these.

•Are you living with chronic pain? If so, you might benefit from learning pain management strategies. You could ask your doctor if there is a pain management programme in your area that you could be referred to.

•Do you have a healthy pattern of activity? People living with functional neurological disorder (including cognitive symptoms) sometimes get into a “boom and bust” pattern. This is where they push themselves so hard on good days that they then feel much worse for several days afterwards.

It is better to try to “even out” your activity by doing a bit less on good days and a bit more on bad days. Once you have achieved this you can very gradually start to build up your levels of activity.

Using memory aids, like writing lists and using alarms on your phone can be helpful for specific tasks. But try not to become too reliant on these, as it is better to use your memory in as close to a normal way as possible. Sometimes keeping lists etc can use so much attention that it can actually make the cognitive symptoms worse. You might need help to make fewer lists and become more confident in using your memory.

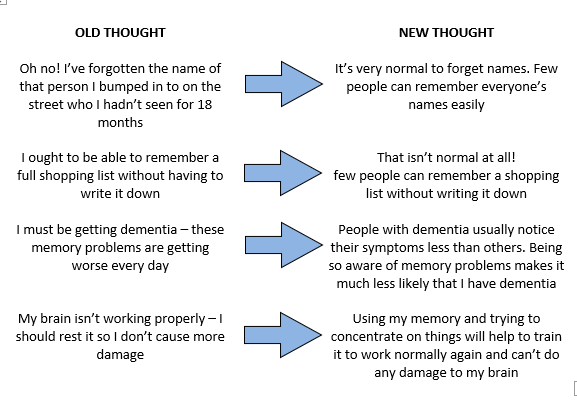

5.Learn to change your own ‘automatic thoughts’ about your memory

Try to start noticing the automatic thoughts that spring to mind when you forget something or make a mistake. Challenging these thoughts can help your memory start to work in a more normal way.

For example:

Although some people can find these self-help strategies useful, we know that it is often hard to make progress on your own without guidance. At the moment, we don’t have much evidence about what is the most effective treatment for functional cognitive disorder. We know that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can help people living with other persistent physical symptoms, like pain and fatigue.

It may well be that this form of therapy could also help with functional cognitive symptoms, but we have more to learn about that.

It is not your fault if you can’t get better by using self-help, and it doesn’t mean you can’t recover. Some neurology or neuropsychiatry departments might be able to refer you for CBT. Ask the doctor looking after you what further treatments might help in your particular case.

In some people, functional cognitive symptoms are part of a ‘bigger picture’ of ill health. Some people with functional cognitive symptoms also have other symptoms of functional neurological disorder (FND). Functional neurological disorders are common conditions that are the result of abnormal functioning of the nervous system rather than nerve damage (software, not hardware).

Some people with functional cognitive symptoms might also have anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Sometimes depression and anxiety are a consequence of the stress of the condition itself.

Functional cognitive symptoms are common in chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome.

Functional cognitive symptoms are also common in people with ‘post-concussion syndrome’ after a head injury. These people might also have problems with headaches, dizziness, and sensitivity to light and sound.

Many people who have functional cognitive symptoms have NONE of these other health problems so please don’t be put off if this section doesn’t apply to you. But if it does, it may be worth spending time with a health professional, such as clinical psychologist, neurologist or psychiatrist who understands these disorders to try and put things together for you.

Josh is 28 and works as a teaching assistant in a special needs school. At work, he was accidentally hit on the head with a table that another staff member was moving into the hall. He was not knocked out, but felt dazed for several minutes after the injury.

For the next few days, he noticed headaches, dizziness and poor concentration. He was sensitive to bright lights and felt extremely tired. He took some time off work to rest. Over the next few weeks, the dizziness went away, his headaches reduced, and he was able to get back to work.

Back at work, he continued to struggle with his memory and concentration. He had previously had an excellent memory, but now found he was forgetting tasks unless he kept a list. After talking to a colleague, he would often realise that he had forgotten most of the details from their conversation. He sometimes called the children in his class by the wrong name, even though he knew them well. He had a sense of “brain fog”, as though he wasn’t quite himself. His thinking was slower, and everything seemed like more of an effort.

The symptoms were worse on days when he had slept badly, or had a headache, but he never felt completely well. By the time he got home from work every day he felt exhausted.

He found these difficulties very frustrating, and was worried about whether he might have damaged his brain in the accident. His GP told him the symptoms could be due to stress or depression, but he liked his job and did not feel depressed.

Josh saw a neurologist who explained that his symptoms were typical of functional cognitive disorder. He was surprised as he had been concerned that his memory problems had been caused by brain damage and might never improve. The neurologist explained that pain and poor sleep interfered with the brain’s ability to focus. He got some helpful tips from a leaflet about improving his sleep. When they looked together at Josh’s activities, they noticed that he tended to ‘overdo it’ on the days when he felt ‘ok’, and this left him exhausted. Josh spoke to the school and negotiated some changes in his hours and responsibilities so that he could gradually build up his activity level at work without this “boom and bust” pattern. Over time Josh’s energy levels improved, and everything started to feel a bit easier. He still sometimes called children by the wrong name, but he noticed that everybody did this sometimes and he no longer felt worried or embarrassed when it happened.

Jean is a 63 year old woman. She has had a hard few years caring for her mother, who died 6 months ago with Alzheimer’s dementia.

She first realized that something was wrong about 3 months ago, when she was at the bank machine and couldn’t remember her pin number. This had never happened before.

She started to ‘drift off’ during conversations and sometimes couldn’t remember things that her husband insisted that he had already told her. She began using a lot of lists, notes, and reminders on her phone, as she felt sure that she was going to miss an appointment. If it hadn’t been for this, she felt sure she would have missed some appointments.

Every day, Jean would find that she had walked into a room and forgotten what she was there for. Although Jean had never got lost when out of the house, she started to worry that this might happen. When she told her husband, he suggested that he should do the driving and that it would be better if they only went out together.

After letting a pan boil dry one evening, Jean stopped cooking and started to buy microwave meals instead, in case it happened again. With everything that was going on, Jean was sure that her symptoms were the first sign of Alzheimer’s disease. She had trouble getting to sleep and would lie awake for hours worrying about the things she had to do the next day, and about how her family would manage as her dementia got worse.

Jean went to see her doctor but did not tell her family that she thought she had dementia as she didn’t want to worry them. It was stressful when the doctor asked her to do memory tests. Her doctor referred her to the memory clinic, where the psychiatrist told her that she did not have dementia. Jean did not feel reassured by this as she knew that something was very seriously wrong with her memory.

However, after another appointment to talk things over with the psychiatrist, she started to notice times that her memory was working very well. She also started to notice when her mind was starting to wander and worry so that it was hard to take information in. She stopped using so many notes and lists – she made a few mistakes with the shopping but not nearly as many as she expected. Jean started seeing her friends again and stopped planning for the worst, although she still sometimes worried about getting dementia in the future.

www.headinjurysymptoms.org

Functional cognitive symptoms sometimes start after a head injury. This website contains information and advice about managing symptoms after head injury.

www.good-thinking.uk

An NHS approved well-being service, with helpful information and resources on topics like sleep, stress, anxiety and low mood

For a scientific review of Functional Cognitive Disorder – see

Date: 25th June 2020

Authors:

Sometimes patients with functional neurological symptoms report quite dramatic periods of amnesia, for example, for a whole afternoon or a whole car journey. This is especially the case in people with dissociative seizures who often have amnesia for symptoms just preceding the attack.

When a whole block of time like this is lost, then the explanation is more likely to be dissociative amnesia. Click on dissociative symptoms to find out more about the general meaning of dissociation.

In dissociative amnesia, the person is not able to remember anything because either

• during the period in question they were either in a trance like state, or

• They are having difficulty accessing normal memories because of a change in function of the brain, which is part of a functional or dissociative illness

We will be re-directing you to the University of Edinburgh’s donate page, which enable donations in a secure manner on our behalf. We use donations for keeping the site running and further FND research.